Recently I asked one of my friends: “How much is freedom of speech worth to you?” He wondered what I meant. “How much would they have to pay you to give it up?” After some haggling, he (a cash-starved law student like myself) conceded that a lump-sum payment of $50,000 would suffice for him to give up the right to criticize his government for the rest of his life.

I then inquired what it would cost to make him agree to be confined, for the rest of his life, in a luxurious prison. The prison would be well-equipped to meet his daily needs, I assured him. Exotic food and drink a la carte would be served around the clock. His 2-bedroom cell will have a window wall overlooking a lake. Gorgeous women would be available on short notice to gratify his desires. And while he would be required to perform some legal research for his jailers, the work hours would not be as onerous as they are in all big New York law firms.

“You’re nuts,” he interrupted me before I had a chance to finish. “You can’t pay me enough to agree to live like that. And besides, I would never get a chance to spend the money anyway!”

I realized that I needed to make the hypothetical more complicated in order to make him agree. So I introduced more variables into the equation. I asked him to assume that his mother was seriously ill and needed a liver transplant that he could not otherwise afford. I also told him that, after 10 years of servitude, he would be allowed to leave the prison, withdraw the accumulated paychecks from his prison bank account, and enjoy spending these savings.

His eyes dimmed a bit. An uneasy pause ensued. “I guess I’ll have to think about it,” he uttered. Freedom had a sale price after all.

Having established that he would be willing to sell his freedom in some circumstances, I pressed further. I asked him to forget about the dying mother and the 10-year limitation, neither of which was relevant for my last hypothetical. Now I simply asked him to assume that he was poor, alone and starving to death, and there were no other jobs available. Would he now agree to live in the luxurious prison?

“Of course,” he replied. “Doesn’t sound like I have any other choice.”

****

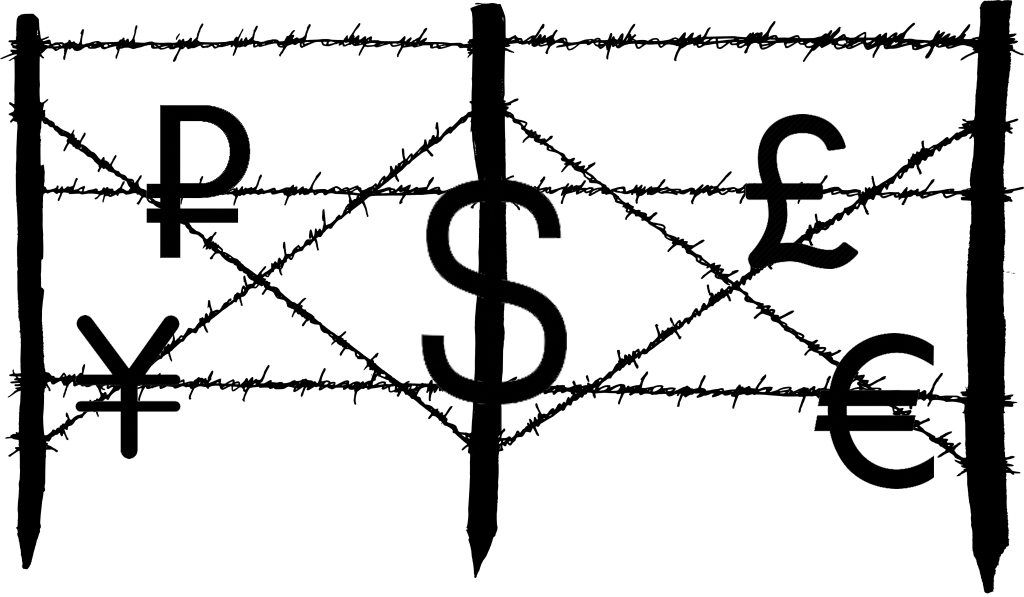

My experiment simply confirmed the obvious. Freedom is not a part of the basic package of human needs. People have lived without it for centuries, and continue to live without it in many parts of the world today. And those who do have it would be willing to bargain it away under economic duress. In a theoretical two-dimensional world where people must choose between freedom and food, people would quickly relinquish their freedom if they did not have enough food. Freedom is not worth much to a starving person.

Extending this idea further, one must agree that, in a democratic society, human attachment to democracy is at its weakest level among the poor. A politician who could credibly offer a sizable increase in their standard of living would be backed by the destitute layers of society, even if that politician advocated establishing a totalitarian dictatorship. Few among Hitler’s supporters had any illusions about what would happen to the embryonic German democracy once the Nazis prevailed. They voted for Hitler because they thought he would make Germans better off, albeit less free.

We see this theory at work today in East European and former Soviet nations, where Communists continue to draw significant electoral support. Their supporters have lived under Communist tyranny before and know full well what a return of Communists to power would mean. Yet they cast their ballots for their old tormentors, and against democracy, because they believe that the newly-installed capitalist economic system has made their lives worse. Not surprisingly, the people voting for Communists in these countries are overwhelmingly poor. One does not find many members of the rising middle class at Communist rallies.

Vladimir Lenin understood this phenomenon perfectly. In 1917, he found fertile ground in a Russia ravaged by war and famine. He targeted war-weary soldiers, hungry workers, and disenfranchised peasants. His promises were simple: “Land, Peace and Bread.” Notice that he did not need to add “Freedom” to capture the hearts and minds of millions.

Prosperous nations do not rebel. That is why democracy has usually taken root and survived in countries that offer their citizens a decent standard of living and ownership of property. Private property makes one a stake-holder in the current system. The owner of a house is not likely to start a riot which might cause his house to burn down.

On the other hand, a starving homeless person living in a shelter is more likely to participate in a riot, because she has nothing to lose. The current economic system has not given her any incentive to defend it. On the contrary, she (just as Lenin’s disciples) might be eager to overthrow it in the hope that a different regime might offer her a better life.

Therefore, the greatest danger to any democracy is its underclass. The poor are least likely to defend democracy in a moment of crisis. They are the ones most willing to sell their Freedom in exchange for much-needed Land, Peace and Bread. Like my law school classmate, they don’t have any other choice.

****

America today is a relatively prosperous country. However, the long-term survival of her democratic institutions will depend on her ability to provide for her growing underclass. The war against welfare, as well as the continued influx of legal and illegal immigrants without an adequate supply of jobs to accommodate them, are hardly steps in the right direction. Those who keep the immigration floodgates open in the face of stagnant real wages are simply boosting the ranks of the army of dissatisfied poor. Even more short-sighted are those who slash away at our social safety net in a fit of budgetary austerity. By cutting off the lifeline of those who need it most, they are sowing the seeds that one day may be harvested by an American Lenin or Hitler.

Vadim Mahmoudov

October 5, 1997