Whenever I see news reports from Ukraine, I remember my family history.

Growing up in Leningrad, the best days of my childhood were spent at our summer dacha in Gorkovskoye. In July, when the nights were white and the air was hot, the best place to be was a lounge chair under our birch tree. We had a tiny plot of land 40 miles north of the city, in a small village surrounded by mighty pine trees on all sides. When the wind blew, the majestic ocean of pine trees swayed gently from side to side and you could hear a soft rumble in the sky. Maxim Gorky had his dacha nearby long ago, hence the village’s name. He picked his real estate wisely.

Our plot of land was smaller than most. It was really a half plot, because the original plot had been divided in two by a tall fence. On the other side of the fence lived the Bad Neighbor with his family.

Our house was also split in two halves. On the other half, carefully walled off, lived the Bad Neighbor. In our family, that was the only term ever used to describe him.

His family was, not surprisingly, named the Bad Neighbors.

We never spoke to them.

Well, that’s not entirely true. Sometimes they would hurl insults at us across the fence. Mom or Dad would curse back at them.

Sometimes they would throw trash across the fence. Sometimes, when nobody was looking, I would decorate their tomato patch with an accurately launched dead mouse that we had caught earlier in one of our mouse traps. I was taught to hate them, though for a long time I didn’t know why. When your parents tell you that someone is the Bad Neighbor, you don’t question them.

The head of Bad Neighbor’s family was a grey-haired dignified man with the stiff posture of a former soldier – the Bad Neighbor himself. Sometimes I would catch him glancing wistfully at me across the fence when he sat on his porch. But he never spoke to me.

The fence cut straight across the original square plot, making each half a narrow rectangle. In the middle of the fence (the center of the old plot that had now been divided) was an old well, shared by each side. A leftover relic from the prior era, when the plot had not yet been split up.

We did not trust the Bad Neighbor with our drinking water – what if he tries to poison us? So we only used the communal well for irrigation water – to sustain our strawberry patches and flower garden. For drinking water, a separate well was dug – entirely on our property – by some handy locals who got paid a pretty penny by Dad. Even though it was done when I was very little, I remember the digging of our new well – it was a big project. Dad was happy when it was done. “Now we don’t have to share our water with that scum anymore.” The Bad Neighbor, not to be outdone, dug his own well in his yard too. So now we ended up with three wells – one for each side, and a communal one that eventually fell into disrepair because it was stuck in no man’s land. Neither side felt responsible for maintaining it, and neither side wanted to use it much anymore. Not a model of economic efficiency, but under the circumstances this whole arrangement seemed to make sense.

One weekend in September, when we were supposed to take the train from Finland Station to the dacha to enjoy the mushroom picking season, I got sick and we didn’t leave the city. That Friday night, Bad Neighbor’s adopted son Oleg and his high school buddies threw a party on their side of the house. They had just been drafted into the Red Army to go fight the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan, so this was their last hurrah before shipping off to Kandahar. They spent all weekend amusing themselves with Bad Neighbor’s collection of hunting rifles, shooting round after round into the wall separating our side of the house from theirs. Later, we spent months fixing the bullet holes.

This was the end of my happy childhood. That summer, we decided to forego Gorkovskoye and the shady birch tree. We rented out the dacha to someone else, and spent our own vacation renting a couple of rooms in a farmer’s cottage in nearby Estonia. We wanted to be as far away from the Bad Neighbor as we could afford to be. Estonia was a fine place, but it wasn’t quite home.

When I became a bit older and more curious, I started asking my parents about Bad Neighbor: what was his real name, and how it came to be that we shared a house and a plot of land with such monsters. Mom didn’t want to talk about it. One day, finally, Dad relented and told me the story. It turned out that Bad Neighbor was my grandfather.

* * * * * *

Fedor Ivanovich Kozhin was a stern Red Army officer who had fought the Germans during the entire War, and a long-time member of the Communist Party. He made a good living as a military radio specialist, and by all accounts was a conscientious hard worker and a man of few words. A few years before Mom and Dad got married, he had a falling-out with his wife – my grandmother. He found a new woman. Mom took the side of her mother, and stopped speaking with him.

The divorce was messy. There was a trial and a division of marital property. Fifty-fifty. The house he had built with his own sturdy hands, and the land on which it stood, had to be chopped up into two halves.

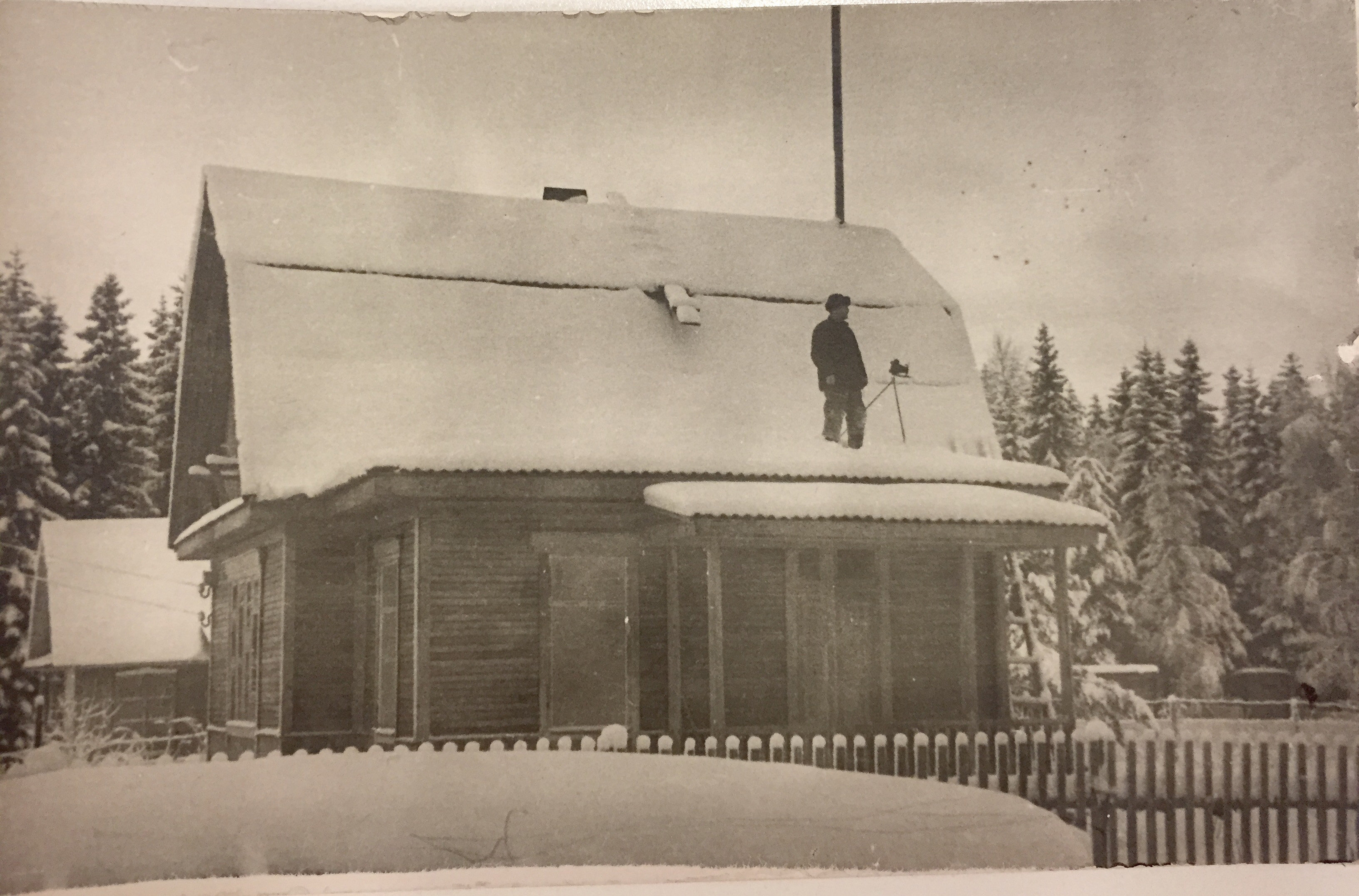

Fedor Ivanovich must not have felt happy about that. I have a faded photo of him in his earlier, happier days, standing on a snow-dusted roof of his newly built house, surveying his little empire. His masterpiece, the exclamation mark of a life well-lived. Now he had to give up half of it to his ex-wife.

When the land surveyor came to mark the property for division, my grandfather put up his last fight. He did not want to give up his favorite second floor of the house, which contained his study – a brightly lit room, facing West, with a panoramic view of the pine treetops that sparkled in the hazy red sunset. Fedor Ivanovich was well aware of the court decision, but was not going to give up easily. He charged grandmother – his former wife and the mother of his children – with his fists.

Fortunately, he did not resort to his hunting rifles, which otherwise could have made matters much worse.

My side of the family responded in kind. Dad, newly wed and generally a mellow dude, was short on military experience but highly motivated to prove his chops to his wife. He also had the age advantage, still in his prime at 29, while Fedor Ivanovich was already grey-haired and over the hill. A life of hard work and four years of war had taken their toll on him. Dad punched him in the face and knocked him out cold. Grandfather’s glasses fell to the floor. To rub salt into the wound, Mom – his daughter – stomped on his glasses with her shoes until the lenses shattered into small shiny shards.

This was the last meeting between the two sides of the family. The house and the land plot were partitioned, and the fence was built, soon thereafter. My grandmother was broken by the whole experience. She passed away quickly after that, a year before I was born. Needless to say, my grandfather never got to hold me in his arms.

********

Decades from now, Ukrainian and Russian historians will be parsing through the chronology of the current fist fight between the two nations who once shared a common home. I doubt you will get an impartial account from anyone.

It is unlikely that militant nationalism will ever be vanquished on either side. So we will probably end up with two drastically different, competing versions of “the truth” – each describing the other side as the angry grandfather who wouldn’t let go.

Ukrainians will say that it was unreasonable for Russia to try to keep Ukraine in its orbit. It was time for Russia to accept the divorce, and the loss of the sunny room upstairs.

Russians will retort that, having decided to go on her merry way, drifting off towards the sunset in the West, Ukraine had no business trying to hang on to Crimea or Donbass. Both are mostly populated with millions of ethnic Russians. Many of them did not support the new regime in Kiev and did not want to remain members of a new Ukraine that had turned decidedly hostile to Russia.

Each side will advance its arguments, stomp its feet and assign blame. Nobody will admit fault, even though there is plenty of blame to go around.

Russia’s little green men should never have invaded Crimea. Maybe it was going to secede anyway, but such processes should not be expedited with outside intervention.

Ukraine’s artillery should never have shelled the streets of Donetsk. Not even Yanukovich ever went that far in his efforts to suppress dissent.

Putin should not have given his blessing to Strelkov and his gang of renegades when they set off to seize the Sloviansk town hall. It was a desperate bid to breathe life into a bogus made-for-TV rebellion that was not catching enough fire in an already troubled land, where most people were still trying to salvage a dysfunctional marriage.

Poroshenko should have told his “cyborgs” to retreat from the airport before the roof caved in on them, instead of stubbornly leaving his boys in place to kill and to die. He was clinging to a symbolic but useless chunk of charred metal in a lost city that turned decidedly against Kiev after months of shelling by his army. Just like his Kremlin counterpart, spilling needless blood for the sake of an inspiring TV drama that kept his nation riled up for a hopeless war.

Whatever. Blah, blah, blah. With apologies to the fervent supporters of both sides, I cannot find a good guy to root for in this story.

The thing I find most troubling is that children on each side will grow up being taught to hate the Bad Neighbor.

******

Decades from now, will Ukrainian children be taught that the Bad Neighbor lives across the fence? Most of them will hardly speak any Russian by that point, since that language will not be taught in their schools. Russian TV and Russian movies will remain banned from Ukrainian airwaves and cinemas, so they will never learn who Cheburashka was. Hopefully, they will not grow up cowering in cold basements while Russian air strikes thunder overhead.

What about Russian children – including those unlucky enough to live in a ruined Donbass, which (with apologies to my Ukrainian friends) is unlikely to pledge allegiance to Kiev ever again? They will grow up in a bitter land, poor and hungry, probably still presided by some stern man. He will rule with an iron fist, and will maintain a monopoly on all TV channels. He will make sure they learn early and often that Ukrainians are not merely the Bad Neighbor, but are also Devil worshippers who wear swastika tattoos and crucify Russian babies alive.

I hope that, one day, this stupidity will end.

It makes no sense for these two neighbors to treat each other like this, even though the fence will always be there from now on.

One of the greatest regrets of my life is that I never spoke with my grandfather.

******

Sooner or later, the guns will fall silent, as they do at the end of every war. There will be no winners, only losers. The few shell-shocked residents who rode out the storm will emerge from bomb shelters, grimly survey the damage, and begin sweeping up shards of broken glass. Just like my parents did after their epic battle with Fedor Ivanovich.

The lucky ones, though still alive, will be crippled. Their souls will retain ugly scars.

I still believe it is possible – indeed, inevitable — that these scars will heal. That both sides will slowly crawl out of this mess and find something in common with each other.

It could be that both countries will ultimately be ruled by wise people, who will have the courage and the skill to reach out to each other across the fence and bridge the gap. But, given the historic paucity of wise leadership on either side, I am not holding my breath for this scenario.

More likely, it will be shady men sporting leather jackets and gold teeth that find a common language. Money cures many disputes. I believe the ultimate reconciliation will be fueled by financial motivations. A complete economic divorce is tremendously inefficient for both sides. The two countries’ economies have always been intertwined, and each remains the most logical trading partner for the other. It makes no sense to dig three separate wells, when sharing one can do just fine.

Even now, every once in a while when artillery raids calm down, trains loaded with coal slip quietly from the rebel territory into the rest of Ukraine. Because Ukraine needs coal, and Donbass needs money, and the crafty middlemen on each side can always use a small fee for helping the transaction go through.

The alternative – cursing across the fence at each other and periodically throwing garbage into each other’s yards, like my family did – or like the Israelis and the Arabs have been doing for several generations – is just too gloomy to consider. I would like to think our two nations can do better than that.

******

When I get to the Other Side, the first thing I hope to do is to find my grandfather.

Who cares if he was the Bad Neighbor in his prior life. That was a long time ago.

I keep dreaming that we will meet under that birch tree, where I sat alone in my lounge chair in my childhood — while he stared at me across the fence. He will finally get up from his porch and stride slowly, with his awkward military gait, towards the fence. Then he will methodically rip the fence apart with his old soldier’s hands.

And I will get up from my lounge chair and run to him across the strawberry patches that Mom had carefully planted, squishing a few berries with my tiny five-year old feet along the way. I will jump into his arms. We will give each other a long big hug, and will be together at last. I will feel his harsh grey stubble pressed against my forehead, his warm tears dripping down on me. We will go over to his side of the yard and sit on his porch, and he will tell me war stories.

Because, after all, he will always be my grandfather. Everyone deserves a grandpa’s hug at least once, and I never got mine.

I can only hope that, one day, Ukrainians and Russians will feel the same way about each other. At this point, it may not be this generation or the next one, but there’s always some hope for the grandchildren. Maybe they will learn to forgive their grandfathers, just like I forgave mine.

Vadim Mahmoudov

February 14, 2015.