Mama had the eagle eye for chanterelles. Marching through the dense forest near our summer dacha, she would often stop and point.

“Right there, under the birch tree.”

To be fair, they were not hard to spot. Yellow clusters in a sea of green. These days, I see them on sale for $29.99 for a quarter pound at Citarella. Back in Gor’kovskoye, in the suburbs of Leningrad, they could be picked for free. All one needed was patience for a long forest walk, a pair of good eyes, and an innate sense of where to look.

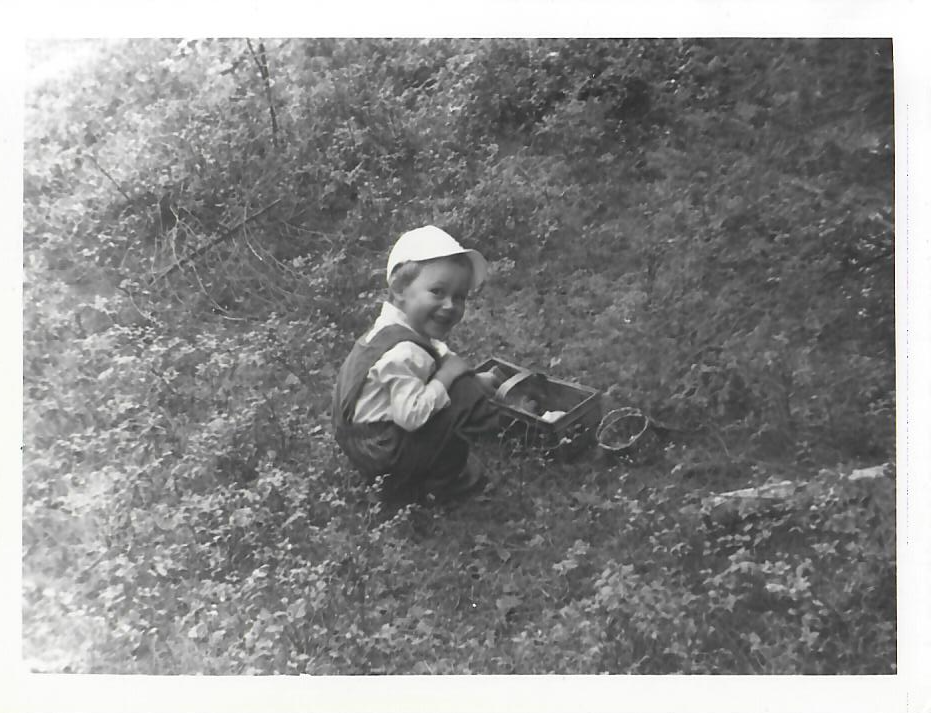

My little wooden basket was quickly getting full. Five years old, I was Mama’s proud helper. In addition to the basket, I had a glass jar with a twist-on metal lid and a wire handle (for picking berries, which needed their own delicate container), and a small switchblade knife for cutting down the mushrooms. You should never rip mushrooms out of the ground. Instead, you cut them at the stem and leave the roots in place, firmly planted in the soil.

“Always check the stem for worm tracks. And cover the roots with moss,” Mama taught me, watching carefully as I unfolded the knife under close supervision. “This way, they will grow back again.”

We were not killing the mushrooms, just harvesting them. Until the next generation grew up.

Mama’s eco-friendly strategy bore fruit many times. I had a favorite spot near the entrance to the forest, by the fallen tree. At least twice a year, I found a lone porcini mushroom there, peeking out among the stems of grass and smiling at me. A lucky charm to kick off our latest mushroom hunt.

Then there were the berries. Blueberries were ubiquitous, scattered in bunches across the mossy mounds, usually among fir trees. They filled up most of my berry jar. Less common were the wild raspberries and strawberries.

We knew another spot in a different part of the forest, on a wide meadow, which always greeted us with neatly organized parallel rows of very rare yellow raspberry bushes and a cherry tree. Unlike most cherries we ate that tasted sour, these were sweet. The abandoned orchard was a remnant of the Finnish civilization that used to own this land, before they fled the advancing Red Army. All that was left of the Finns, aside from the berry plantation, was a rectangular stone foundation of a house that once stood there.

“They didn’t want to leave anything behind for the Russians, so they burned the house.” Mama had a vivid imagination and story-telling ability, and I eagerly gobbled up her interpretation of history, as if she were there in 1940 when the house vanished in a blazing inferno. For all we know, she was probably right. “But they couldn’t destroy the raspberry bushes.”

Thirty-six years later, the bushes lived on. We would shake our heads at the Finns’ vengeful tenacity, thank them for leaving behind a rich bounty of well-cultivated berries, fill our jars and move on.

The forest still bore scars from two wars that passed through it four decades ago in rapid succession. First the Winter War, then World War II, when the Finns teamed up with Hitler and tried to get their land back. There were several huge bomb craters near the road, now filled with putrid stale water and garbage. Deeper in the forest, in Boikovo, we often passed an angular trench and the remains of a dugout hear the hilltop. A modest memorial stone named the soldiers who were buried there.

In a nearby pine grove, while walking down a popular trail wide enough for vehicles, looking closely through the trees one could spy a rocky dzot (fortified fire point) hidden in the corner of the forest. The dzot had a clear side view of the road: a perfect spot for an ambush. An unsuspecting enemy, riding up the hill, would drive around the bend and get pulverized with machinegun fire.

Now the dzot’s ruins were also filled with garbage, and the forest was peaceful, ruled by a grumpy black moose. The moose didn’t care about wars and international borders. He just left huge piles of dung all over the place. We kept a respectful distance and continued our vegetarian foraging trip.

* * *

In the evenings, back at the dacha, Mama cooked a feast.

Mulled wine was simmering in a red pan on the fireplace stove. The sweet and smoky aroma of cinnamon sticks, cloves and nutmeg was itself intoxicating. Who knew alcohol could be so tasty?

The star of the show was a wide frying pan, filled with our loot from the mushroom hunt. Chanterelles, porcini, and russulas, now washed clean and chopped into pieces, danced together with onions and garlic on a bed of molten butter. To add a little more protein, Mama would toss in a few chunks of salo (pork lard), which turned into delicious cracklings.

Potatoes were cooked separately in a different pan. Mama had an infinite menu of potato varieties. Sometimes she made shoestring French fries; other times, chunky home fries. On a different day, we got fluffy mashed potatoes. On a busy day, plain boiled potatoes, slightly browned in the frying pan at the end of the process, still got the job done. Everything was sprinkled with a dash of pepper and salt, and the main course was complete.

If guests wanted more meat, Mama offered many chicken dishes. Roasted Cornish hen was a fan favorite, as were fried chicken livers, but I had a soft spot for chicken soup. In the bouillon, spiced with herbs, floated the lesser-known parts of the chicken that you wouldn’t find in a traditional Western supermarket: the heart, the neck, and of course chicken feet. I loved gnawing on the tender chicken paws and fingers. Years later, when we settled down in Brooklyn, Mama and Papa could never understand why these parts were removed from the chicken that was put out for sale. “You need to use the whole animal, that’s why it’s there.” Foolish Americans…

Well before I was born, Mama faced another clash of culinary cultures when she was digging up ancient ruins in Georgia with a group of fellow young history students. Exploring an alpine forest in the mountains, she found a treasure trove: a massive colony of porcini, truffles and morels. She gathered as many as her coat pockets could hold, then hurried back to the house where her team of archaeologists was staying. Mama started to rally the troops for an urgent mushroom hunt. Quickly, before someone else comes and picks them off!

“We don’t eat those,” the old Svanetian landlady shook her head. “They are bad for you.”

Mama could not believe it. Yes, some mushrooms can kill you. (Others can produce deep thoughts and hallucinations, as I learned in my college days.) But anyone who spent some time in the Russian woods knows not to pick the red-capped Mukhomor, or the grey and slimy Blednaya Poganka. Come on!

“Well, I guess this means more food for the rest of us,” Mama shrugged, diplomatically agreeing to disagree. And she headed back out with a big basket to gather the precious harvest. The superstitious Svanetians had no idea what they’ve been missing out on.

Still shaking her head, their local host required that the worst frying pan in the house be used for cooking the meal. She did not want her better cookware soiled with the suspicious mushrooms.

That evening, the visitors ate like kings.

* * *

Mama had a horrible childhood. The Germans invaded in June 1941, when she was seven years old. Her family was trapped in Leningrad, which was quickly encircled by the Germans from the South and the Finns from the North. Suddenly, Mama – a helpless child – found herself in Hell, with no way out.

The city was bombed and shelled, day and night, while the surviving residents cowered in underground shelters without running water or electricity. As winter set in, food began to run out. Frozen corpses littered the streets. Mama watched her family starve and die around her, barely alive herself, and learned a bitter lesson: life sucks when there is not enough food.

If you could make your way to a food distribution station, the daily ration was meager. 250 grams of bread for a manual worker; 125 grams for any other civilian, like Mama. An “eighth” of a kilo. No meat. No mushrooms. No dairy. No fruits. Good luck surviving on one piece of bread a day.

I cannot imagine the debilitating hunger they felt, and hope never to experience it myself. Mama survived, but lost both of her siblings and her grandmother, and was mentally scarred for life. She later described the nightmare in excruciating detail in her autobiography. But there was one story she told me that didn’t make it into the book. Maybe it was too painful for her to write about it.

After the war, she returned to Leningrad and went back to school. One of her classmates, another eleven-year-old girl, had grey hair like an old lady. It might have been due to lack of nutrition and vitamins during the siege. Or it could have been watching her mom die in slow motion, eaten by rats.

The siege was tragic not only for humans, but also for Leningrad’s rodent population. In a half-empty city, with restaurants and markets shut down, and the hungry survivors leaving no food scraps behind, there was not much left to eat for the rats and mice. The crafty animals turned to scavenging on stiff frozen bodies, but that’s a hard meal in -40◦ C weather. Rats don’t know how to cook.

Mama’s friend was sitting with her mom in their apartment, paralyzed by hunger and exhaustion. They had just gone out for a long walk to pick up their daily eighths, and were now warming their frostbitten feet by the little burzhuika metal stove. After the central heating system had collapsed, this was the only source of warmth. The stove’s heat attracted the desperate rats.

The rats approached their feet and sniffed cautiously. The daughter still had enough strength to pick her feet up off the ground and curl up in her chair. Her mom remained motionless. Then the biggest rat took the first quick nibble. Mom moaned, but did not move. So the rats started gnawing away.

If she had had any energy left, she could have chased away the rats. Maybe even caught one and made a meal out of it. But she was too weak to fight for her life, or no longer cared. That day, the rats had a feast of warm human flesh. Rats need to eat too!

Most of us spend our lives eating other animals. Sometimes, the tables get turned and the animals eat you. It’s nature’s ultimate revenge.

Decades later, when I was a little boy, the city still had scars of war, just like the forest near our dacha. The south side of St. Isaac’s Cathedral was pockmarked with traces of shrapnel. On a side street, a blue sign advised pedestrians: “During artillery raid, stay on this side of the street.” But the one I remember the most is Anichkov Bridge across the Fontanka.

The famous bridge is made of pink granite and features four bronze statues of men in various stages of trying to tame a horse. During the war, the statues were removed from their pedestals and buried in a garden nearby. Wise move, because the bridge soon came under intense artillery fire.

After the war, the horsemen returned to their pedestals and most damage was repaired. Except one place, left as is, on purpose. One of the pedestals still has a large dent, commemorated with a plaque. A shell must have hit it on the side, biting off a chunk of stone. But the sturdy bridge remained standing.

“The Germans thought they could break us,” Mama said once when we passed the wounded pedestal. “But we were stronger than them.” And a rare sly smile crept across her face. Silly Germans, trying to conquer granite with cannons.

Mama was not a big fan of the Soviet government. She read banned books and listened to Voice of America. But when it came to World War II, she was still an avid patriot of her country. Russia was unbreakable and immovable, like the granite monolith. And she loved it.

* * *

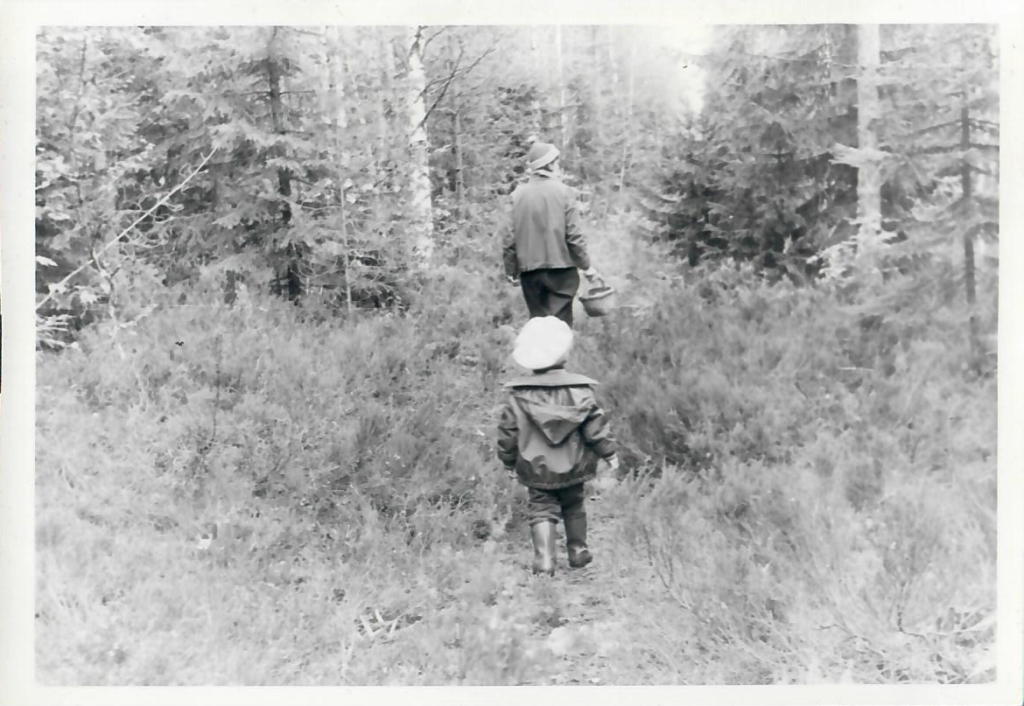

“Always go to the mossy and moist places. That’s where blueberries tend to blossom,” Mama was storming the swampy part of the forest in her tall rainboots, walking briskly and smacking aside dense bushes with a long wooden cane, as I struggled to keep up. She was determined to teach her only child how to live off the land.

I didn’t like the swamp. It was dreary and dark, and you had to be careful where to step, probing the ground with the walking stick. The terrain was treacherous. A big mossy patch might have solid ground under it, or… it might not. Then my boots would sink deep into the muck, and a hasty retreat was in order before I could get sucked in deeper. But the worst part was the mosquitoes.

No story about a Russian forest would be complete without discussing The Bugs. Legions of mosquitoes swarmed all over us, singing their whiny songs in our ears, no matter how much insect repellant we put on ourselves. We wore hats and several layers of clothing, but the hands, neck and face were still exposed. I usually came back itchy and grumpy. Aside from mosquitoes, there were also wasps and hornets buzzing around, occasionally landing on us. A huge bumble-bee stung me in the cheek once, and I had a welt the size of an apricot for a week.

All that suffering, just to fill a few jars with blueberries. But Mama was stoic and unstoppable. Winter was coming, and we needed to stock up for it. Once the ground froze and the snow fell, there would be no more trips to the forest. We would be back in our little apartment in Leningrad.

I understood it, in retrospect, many years later. People who grew up in poverty keep an eye on their “rainy day” slush fund. And people who grew up hungry in wartime stock up on food. Just in case the dark days return again. Because you never know – they just might.

* * *

When the leaves outside turned yellow, Mama’s massive food preservation operation kicked into high gear. Berries were cooked into delicious pies, encased in sugary flour. Big jars of blueberry, raspberry and strawberry jam lined the shelves. On the windowsill, facing the sunny side, stood a row of bottles densely packed with cranberries, spices and sugar. They slowly fermented to produce a strong infused liqueur a few months later.

A long row of porcini mushrooms also dried in the sun near that window, pierced by a long wire, shish kebab-style. After they had shriveled enough for a few days, Mama and Papa would take them off the wire, thread a needle through the holes, and hang them up on strings in the sunlight like Christmas tree decorations. Now we had an ample supply of dried mushrooms for creamy winter soups.

Greyish milkcaps also needed special treatment. They are disgustingly bitter, and not edible in their natural state. But pickle them with salt and garlic for a couple of months in your refrigerator, and now you have a perfect vodka snack for those dreary winter nights!

At the dacha, our plot of land was not huge. It was made even smaller by Mama’s garden. She inherited it from her mom, who survived the war with her, and maintained it religiously whenever she was not in the woods hunting mushrooms. Often, I got long lessons on how to water plants or dig up soil.

In addition to gorgeous flowers that impressed all our guests, the garden had a utilitarian side. Rows planted with potatoes, radishes and carrots were followed by a small grounded greenhouse, where strawberries, cucumbers and tomatoes were protected from the elements. In the back, a dense patch of thorny raspberry and gooseberry bushes clustered next to an epic apple tree that leaned into our yard from the neighbors’ side of the fence. On a lazy summer day, one could survive without going anywhere else by simply foraging in our garden.

Mama’s little empire came in handy in the early 1980’s, when the country again fell on hard times. Suddenly, one day there was no meat in the supermarkets. “Not even those nasty liver sausages that people feed to their cats,” Papa reported after a failed shopping trip. The Soviet economy was showing the first signs of collapse.

“That’s OK, we still have plenty of potatoes and butter,” Mama’s voice was firm and cheerful. “We’ll just pretend that the butter is the meat!” She had seen much worse. And we also had a ton of jars of canned food, stashed away from last autumn. Deep inside, she probably thought: Here we go again.

All these years, she knew this was coming. Bad times have a way of coming back, sometimes very quickly. And now the Queen of Mushrooms was smiling defiantly, ready to face her next challenge. She will think of some way out.

* * *

“Always wash the dishes soon after eating,” Mama preached, as I was helping her rinse out dirty plates and frying pans in the soapy sink in our small Brooklyn apartment. I was now in college, taller than her. “Otherwise, the grease and sauce will become much harder to scrub out later.”

“But Mama, come on,” I protested. “After dinner, everyone is happy and mellow. Wouldn’t it be better to entertain guests, and take care of dishes a few hours later?”

“A few hours later, after you’ve had three more beers and a joint, you would be even less motivated to clean up anything,” old wise grey-haired Mama winked at me. “I know what you guys do, down there in Georgetown.”

We had left the Soviet Union seven years earlier, and were now waiting to have our American citizenship approved while our former country was imploding far away. We no longer had a dacha, there were no woods outside our dreary apartment building on Ocean Avenue (or anywhere else nearby), and we were living on foodstamps. But on a positive note, I was getting a university education instead of being conscripted into the Red Army. And there was plenty of good cheap food! New York City did not suffer shortages of meat. We were poor, but never hungry.

Her fast-walking berry hunting days were behind her, and Mama now focused on cooking new recipes, blessed by a smorgasbord of ingredients that she never encountered before. She became a fan of Mexican rice, Italian spaghetti and Indian curries. She pounded breaded pork schnitzels, simmered veal stew in an oval metal pot, and sometimes even made juicy short ribs that fell off the bone. For Thanksgiving, we did not adopt the local turkey tradition (too dry for our taste), but instead Mama baked a crispy fat duck stuffed with apples. Aside from all that, she continued to refine her yummy chicken dishes.

But she did not love the bland white mushrooms that were on sale at Waldbaum’s. “Boring, no flavor,” she sighed. Even she didn’t have the Midas touch to turn them into gold. Some things were better back home, after all. And we did not have the budget to shop for chanterelles at a fancy store.

Forest mushroom hunters now became urban bargain hunters. “Two dollars for a bottle of Swiss red wine!,” Papa would exclaim. “And it’s tasty too!” Suck it, Opus One.

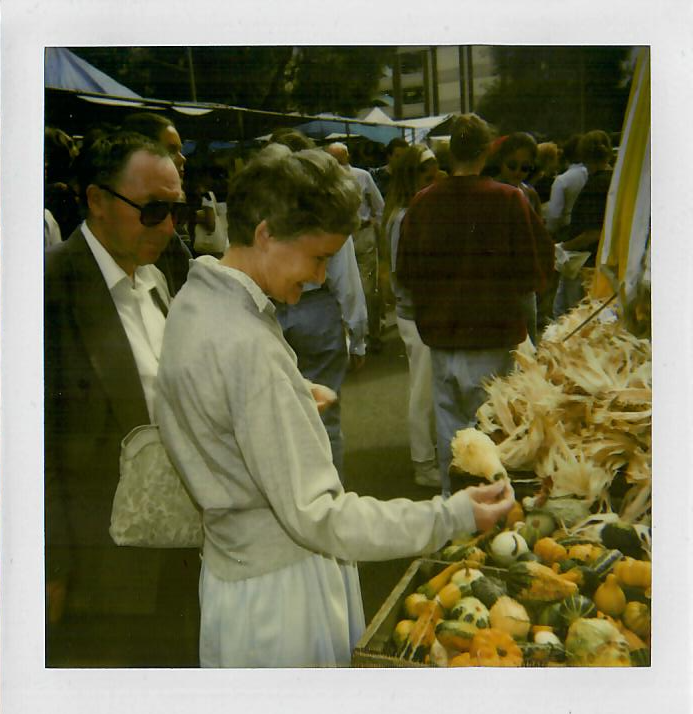

Despite our frugality, we allowed ourselves little pleasures. The Swiss wine was Papa’s weakness. For Mama, it was her tiny collection of flowers, which she sometimes bought on our weekend trips to Manhattan, when we made a mandatory stop at the Union Square farmers’ market. It was a miniature version of the garden she used to grow at the dacha. She dutifully fed all her plants with a long spout watering can, then sprayed their leaves with mist. As usual, they were placed strategically in the sunlight – near the South window, with a few hanging outside.

Her empire had shrunk, just like the queen herself. But it was still beautiful.

* * *

A few years later, it all started going downhill.

One day, she served up her trademark cucumber and tomato salad. But this time, the vegetables felt squishy and soupy. Somehow, Mama’s impeccable quality control in the kitchen was slipping.

“She is starting to forget important dates,” Papa whispered to me as we strolled in Astoria Park, our new neighborhood with charming sunset views of Manhattan’s skyline. “And sometimes she makes up stories from the past that I know never happened.” Back in her prime, Mama, an accomplished art history scholar, had a steel-trap memory and a perfect grasp of historical details.

Even more shocking was her sudden struggle with geography. Back in the woods, no matter how far we wandered, we never worried about getting lost. Mama, a seasoned traveler, had a keen sense of direction and always found a way back. Now, she went to the supermarket, a few blocks away, and then forgot how to return to her apartment. Embarrassed, she called us from a payphone and asked to come get her. At least she still had the home phone number written down…

Eventually, she stopped cooking. Her diet now consisted of Twinkies and cinnamon rolls. Her stomach ballooned and her teeth began to fall out.

She still remembered who I was, but spoke little and spent most of her time in a mild haze, smiling and nodding her head while others in the room led the conversation. A brilliant writer and fierce hiker, who survived the German siege and the Soviet regime, was now a ghost. The body was still there, but the mind was not. She was shriveling, like a dry porcini in the sunlight.

But there were still rare moments of clarity, when the old Mama resurfaced. She would quiz me about my travel plans, or jump in with hilarious commentary on George W. Bush while he rambled on TV. Sometimes, she surprised us with self-deprecating humor, making clear that she was aware of her own predicament: “See, I’m not as crazy as you all think I am!”

During one of those brief moments, she and I were sitting on her little balcony, enjoying the warm spring air. Her plants had found a great new home, the sun shining down on them directly. She was recovering from a week-long stay at the hospital after a nasty kidney infection. Mama was not fond of hospitals. Suddenly, she fixed her piercing eyes on me and made her final food-related comment.

“Vadik, no matter what happens…” She paused, looking down at her wrinkled hands. “I don’t want any feeding tubes in me.”

In the end, we honored her wish.

* * *

During the summer of 2013, a few months after Mama passed away, we took a family trip to Finland. Papa, now in a wheelchair, stayed back in Queens. But the next generations – myself, Alicia and nine-year old Ilan – were now strolling through the Finnish woods, which bore a striking resemblance to the woods I grew up exploring on the other side of the border.

As we walked down a trail from our hotel to dinner in the village center of Naantali, we came upon a densely wooded mossy area. Mosquitoes began to serenade us, and my old instincts kicked in. Looking sideways from the trail, I already knew what I would find. Sure enough, there was a blueberry bush five feet away. And next to it another, and another. We were in the midst of a nirvana of wild blueberries.

We had not planned on making any pit stops. We had no rainboots, basket, or glass jar. But we still had big pockets. I crouched down in the middle of the grass, and started teaching my son how to pick berries. The giant fir treetops gently stirred overhead in the wind, approving our impromptu visit.

And then it all became clear to me. Mama was not gone. She was everywhere – dancing with mosquitoes, helping us spot the next blueberry bush, and climbing the tall trees. The forest had not forgotten her, and was now welcoming back her offspring with open arms.

People are like mushrooms. You can cut down a mushroom. But as long as the roots stay in the ground, it will grow back. We were Mama’s mushrooms. And even after we all end up in the ground, new generations of mushrooms will rise and take our place. The Queen of Mushrooms is immortal.

“What time is our dinner reservation?,” Alicia asked. It was already seven o’clock, but the sun was still high above us, peeking through the trees. It was White Nights season.

“We are three minutes away. I am sure we will be fine,” I did not want to leave the peaceful Northern forest. It was healing me.

“I am getting hungry,” Ilan chimed in. “These blueberries are awesome, but now I need some meat.”

“Then let’s go,” I stood up, and we headed back to the trail. “I checked the menu online, and it sounds yummy. They even have weird things like elk and boar.”

I did not disclose the real reason why I picked that restaurant.

Fricassée of hen of the woods and chanterelles.

* * *

Vadim Mahmoudov

March 12, 2024.

What a wonderful post, Vadim. And a moving tribute to your Mama, may she rest in eternal peace.